In early December of 2020, I powered through A Promised Land, President Obama’s autobiography, part one of an expected two volume set. I tend to avoid reading while I’m actively writing for fear of inadvertent appropriations. But as they say, we can’t live on bread alone.

His book was outstanding, of course. I expected little less from the great orator. While it bogged down a bit with the minutiae of Washington politicking, it was at its most insightful when he relayed what it was actually like to be president behind closed doors.

I particularly enjoyed the finesse in how he rendered his perceptions on race in America, drastically unlike my own heavy-handed form. In one segment, he spoke of the racially charged incident with Professor Henry Gates, a prominent Black American scholar, and Officer James Crowley of the Cambridge Police Department, wherein the latter took the former into custody after Gates gave Crowley a hard time on accosting him trying to enter his own residence (the door was jammed, a suspicious neighbor called the cops). In examining the press buzz over what would become ‘the Beer Summit,’ when he invited both Gates and Crowley to the White House to smooth things over, Obama reminisced on his own experiences with whiteboy racism. He talked of getting asked for identification in circumstances where his white friends did not, unwarranted traffic stops, department store security guards’ scrutiny, and car locks clicking as he walked by, the same old horseshit most peoples of color suffer every day.

It was admittedly disconcerting to read an American president’s experiences following the same patterns as any other Black person. There was a tiny little ingrained whiteboy part of me that erroneously presumed perhaps he’d had a lesser time of it, if he’d reached the executive apex he’d achieved. But no. No, it’s pretty standard. There are few, if any, exceptions to the rule.

Obama went on to mention the fallout of approval ratings from white constituents once he’d denounced the action at a live press conference. The ex-president knew perfectly well how talking racism to whites, even progressive ones, tends to trigger them:

“It was my first indicator of how the issue of Black folks and the police was more polarizing than just about any other subject in American life. It seemed to tap into some of the deepest undercurrents of our nation’s psyche, touching on the rawest of nerves, perhaps because it reminded all of us, Black and white alike, that the basis of our nation’s social order had never been simply about consent, that it was also about centuries of state-sponsored violence by whites against Black and Brown people, and that who controlled legally sanctioned violence, how it was wielded and against whom, still mattered in the recesses of our tribal minds much more than we cared to admit.”

Leave it to Barry to upstage my points herein. I’ll gladly cede my class-based crowing and cawing to forty-four. He’s forgotten more about this topic than I could ever hope to add to the national conversation.

Yet unlike our former rock star prez, I’m less inclined to slow-walk the needed message to whiteboys. Just like our daddies and paw-paws taught us, we learn a lot faster with the existential belt, the ethereal wooden spoon. Whiteboys need a whuppin’ of their souls, not their backsides. They’ve been spared the meta-rod long enough.

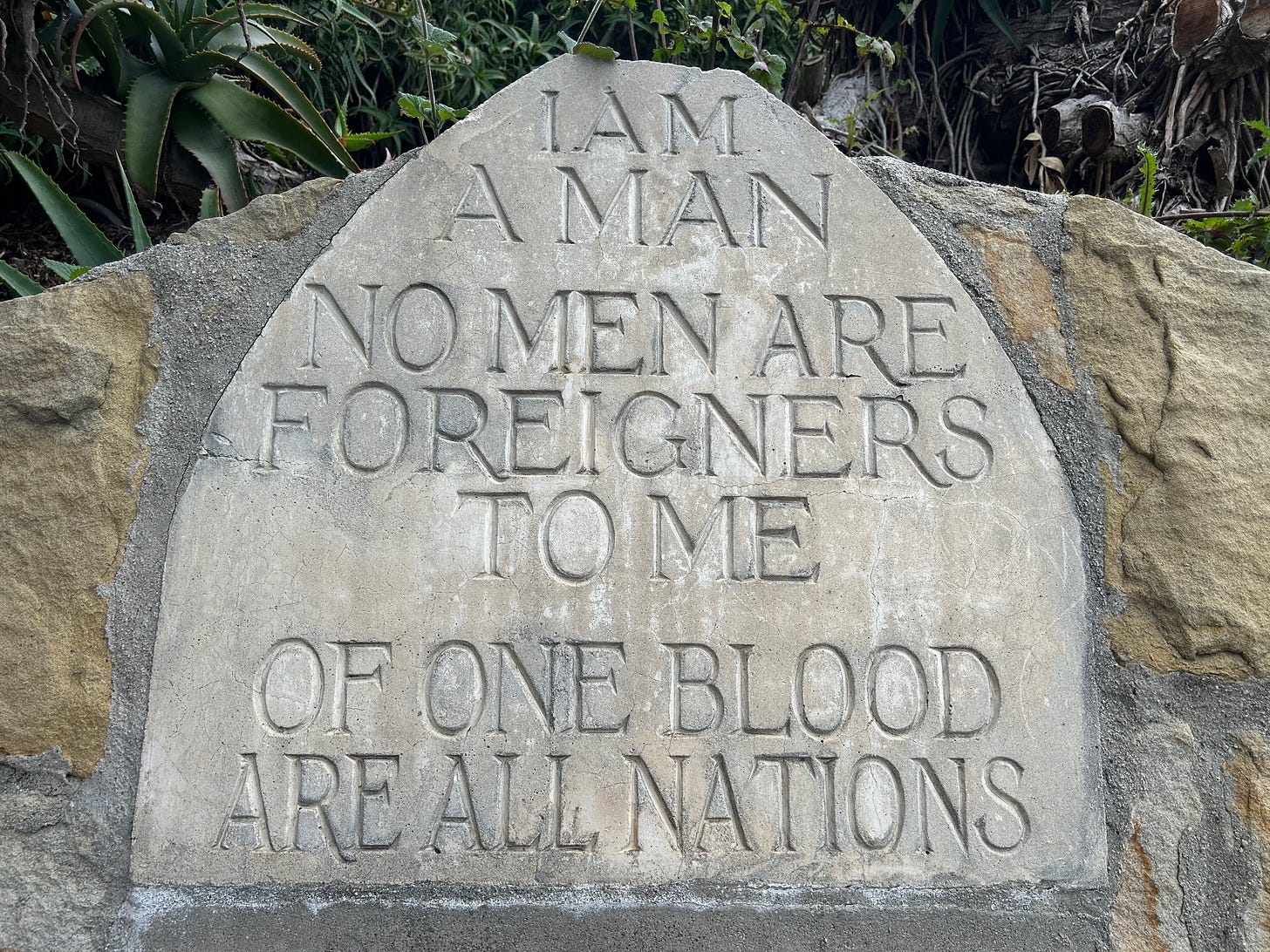

On a walk that day with Dez, in early December of 2020, the same day I penned this entry, I came across an statuary embedded within a wall at the Franceschi House, a local landmark over a century old. Its original architect was named Francesco Franceschi, and he operated a botanical garden and nursery at the location way back at the turn of the 20th century. Then a philanthropist named Alden Freeman bought him out and turned the place into an Italianate villa open to the public. I’m uncertain which one of those guys was the spiritual one in the Christian faith, but it was definitely one of them. Nowadays, the old villa is dilapidated and in various stages of ruin, slated for demolition so that the park around it can be expanded.

I went back there today with my current doggo, Mayday. The deep-cut lettering, chiseled into marble, remains nearly as legible as whenever it was carved. It’s more or less an biblical amalgamation of declaration, its quotes pulling from the Greek bishop Irenaeus, Isaiah 2:4 and 11:6, and Acts 17:26.

I AM A MAN

NO MEN ARE FOREIGNERS TO ME

OF ONE BLOOD ARE ALL NATIONS

NATION SHALL NOT LIFT SWORD AGAINST NATION

NEITHER SHALL THEY LEARN WAR ANY MORE

A LITTLE CHILD SHALL LEAD THEM

PEACE

*Compiled from December 4, 2020