My hometown bangs the drum each year in early August, with a holiday marking a romanticized depiction of California’s pastoral Spanish history.

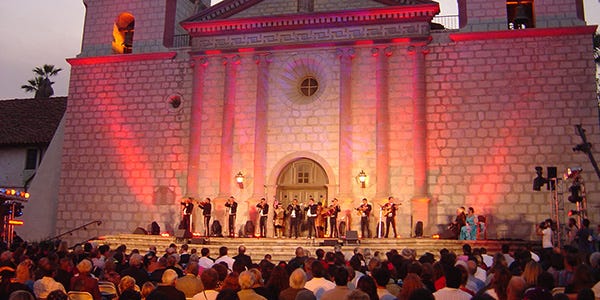

The city of Santa Barbara hosts one of the crown jewels of Catholic colonialism; the Santa Barbara Mission. The hoopla in question is called Old Spanish Days, ‘La Fiesta.’ Local blue bloods and middle-class members alike dress in traditional 18th century Spanish outfits, and head out on the town. They dance and eat and commune for five days, rip-roaring California’s colonial past like it was another glorious, Manifest Destiny kinda deal.

It’s really just another excuse for folks to get loaded and whoop it up and forget the grind of their 9-to-5s, same as most American holidays. Unfortunately, Santa Barbarans by and large ignore the true history of the cultural flashpoint they’re celebrating, which rests on the decimation of the region’s original inhabitants, the Chumash tribe, courtesy of explorer Juan Cabrillo. His arrival to local shores heralded initial European contact, resulting in the subsequent enslavement, rapes, and killings of local Indigenous populations.

Additionally, many Mexican and Chicano first settlers lost much of their original identities through cultural amalgamation, via the church and its missionaries and the unyielding weight of Anglo-Euro cultural spread. Many descendants of those same peoples now celebrate the Fiesta holiday with as much, or more, investment as the whiteboys around town. ‘Fiesta’ in Santa Barbara was appropriated to the modern age as a celebration of Californian and Mexican culture, foregoing its roots in brutality from Euro-Spanish conquest and Chumash genocide.

I know not whether Mexican culture embraces the local celebration because of its roots in Brown-skinned settlers (the Euro-Spanish and the Mesoamerican migrants, rather than the English or the French) or whether they’ve simply tossed out the dirty bathwater much like whiteboys do, figuring they have so little representation among Anglo cultural trends and anything at all is better than nothing. Either way, I completely understand, but…it seems to be another possible example of emulating former oppressors, a kind of Stockholm syndrome frequently observed in conquered tribes. It makes sense. People tend to gravitate toward what seems to be working for the highest caste.

I grew up about a half mile from the local Chumash reservation. The bus to school picked me up at my stop, and the next stop was the depot for the reservation. The Chumash children got on the bus in thrift store clothes and hand-me-downs and sack lunches filled with blocks of government cheese and thermoses of powdered Tang. My mother knew several of the elder wives on the reservation. We’d go out there sometimes to have lunch with them, and while there were decently appointed seventies style ranch homes for some few, there too were an abundance of shacks and dilapidated shanties and a disparity of substandard housing, compared to the rest of my whiter-than-white community outside reservation boundaries.

My small town was too country-rural for legit slums or ghettos, but at the rez, it was a near enough thing. The tribe built a casino in subsequent years and their standards of living increased dramatically, rallied by funds from casino patrons largely consisting of the same white folks who’d marginalized them all those years beforehand.

You can’t imagine how many heated debates I’ve had with white associates who grew up in the same north enclave of Santa Barbara County as I did. When the Chumash first developed their gambling facility, it was little more than a large, tented pavilion with open-air, pay-to-play blackjack tables. Eventually it morphed into modernized architecture, culminating in a twelve-story luxury hotel and casino. Locals were aghast, particularly the ones who owned homes near the reservation, claiming property value declines, decrying the supposed eyesore of the hotel nearby a main highway not far from where I attended elementary school as a child.

I didn’t understand their grousing. Those white homeowners rolled the dice in purchasing land, same as we all do. Somebody could always develop an airport next to your home, or you might find some of your boundaries challenged by county ingress and egress easements, or maybe your original seller-owner buried bodies beneath the basement. Who knows? Either way, crying about whatever the tribe wanted to do with their sovereign lands…the same ones they were forced upon back when whiteboys conquered the area…was outrageously audacious.

Because it wasn’t implicit bias.

It was explicit bias, right there in living color.

More important, as I urged my associates to recall the appalling poverty among our grade school Chumash associates back in the seventies and eighties, it was about fucking time our endemic Indigenous people reaped at first marginal and then eventually epic benefits from the lands they were bestowed. It’s always been a dead red flag to me, the whole resistance to Native casinos in California, spearheaded by Las Vegas corporations and bureaucracies. First we take their lands, then we qualify how they might capitalize upon them.

And the caste beat keeps on drummin’.

Much of Indigenous mysticism speaks to me, perhaps because though I am a descendant of conquerors, by fortune of birth I am rooted to this land as well. My essence is inextricably tied to this small sector of the earth…remember, we talked about sacredness of place earlier in this narrative.

Yet I will never have earthly ties as the Indigenous do.

My perceptions and abilities to bond with place and time are genetically and environmentally shaped by having propagated through white bloodlines. Were it not for the fact I’m attempting to practice whiteboy reformation and thus reluctant to appropriate any culture that isn’t based in my specific tribe’s origins, I’d surely have embraced many Indigenous customs. I remain envious, yet respectful. They’ve had enough stuff stolen from them.

It’s my firm opinion Indigenous and Aboriginal peoples have come the closest in figuring out what the fuck is going on in this universe, what’s important when trying to coexist in balance with Mother Earth and what isn’t important. It makes sense. They’ve been around the longest on their respective continents. They’ve passed down cross-generational conventions grounded in both the natural and the metaphysical worlds. They routinely apply moralities founded in connection and purity of heart.

There’s no question they’ve endured equitable damages as any other race at the hands of European imperialism, perhaps more so, perhaps most of all. I’m not qualified to render degrees about that. Only Native Americans can readily classify their historical tiers of transgression.

If the tent cities of our urban unhoused haven’t convinced you yet of third world maladies remaining in much of the United States, if you’re not swayed by the facts of Indigenous peoples having been forced into impoverished lives from continued white privilege, visits to Montana’s Crow reservation or South Dakota’s Pine Ridge reservation might move your barometer. Not all tribes have the opportunities to build casinos. Too many Native Americans continue to suffer the legacies of white conquest, all these years later.

In any case, American rituals ought not to be based on events stemming from colonial conquest. We can forge new traditions, much the same as we’re slowly doing by giving up confederacy testaments. Just because something’s been happening for an extended period of time to become a tradition, doesn’t mean we can’t change it to respect those who paid for those commemorations in blood.

Our Eurocentric celebrations of empire are their reminders of holocaust.

Scrap Thanksgiving and turkey dinner? Make Indigenous People’s Day in October a federal holiday? Axing the tortas and tequila and cascarones of Old Spanish Days? More of that diabolical cancel culture?

I told you…it won’t be easy.

SENTIMENT.

She’s a two-ton gorilla, ain’t she.

In that late summer of 2020, I discussed Santa Barbara’s legacy and the original Indigenous peoples of its lands with an old associate of mine, a Sʰamala Chumash linguist. She’s a passionate advocate for her heritage and strives to keep her original culture intact by teaching current generations of Chumash citizenry their traditions and languages. Her shared sentiments rightfully eclipsed my own whiteboy observations and she was gracious enough to allow me to share them.

“I’m a member of the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians. We call ourselves Sʰamala Chumash. Sʰamala refers to our location and our language. I am a gaming commissioner at our casino, I’ve sat on our tribal health and education boards, and I work primarily in our tribal and culture department, where I am the lead language instructor, having a teaching credential in the Sʰamala language. My passion and heart lay in my community and my efforts to return what was taken from my people.

In sharing stories, I must always begin with my elders and my ancestors when I speak about the trials we have endured. My grandfather, mother, and her four sisters lived in one of the first federally funded HUD houses on the reservation. There was no running water or electricity and only one irrigation pipe where they collected their water.

Only blocks away, the largely white populace of the Santa Ynez Valley had fully operating utilities and didn’t seem to care much whether we did or not. My mother and our relatives had to raise money by selling enchiladas and hosting Native fashion shows. We did receive occasional assistance from the local mission and a few empathetic locals, but those gestures were scarce.

When my mother and many of my relatives were young, they were told to tell locals they were Mexican because it wasn’t good to be a Native. Many of our prior generations were never taught our Native language. The children were sent outside while the adults spoke the true language.

There are many laments in our culture, even now in the post mission era, of the horrific things that happened to my people, but the one thing that never changed was the racism, the stigmata, the judgment of others on the color of our skin. Growing up in our small town, there were no Natives and very few Mexicans at our elementary school. My brother and I heard all the standard epithets toward those with Brown skin; ‘beaner,’ ‘dirty Mexican,’ and so on.

I am both Native and Mexican. No one in the community outside the reservation, including my white teachers, much bothered to ask about the specifics of my heritage. We few Natives and Mexican kids at our predominately white school all got our free lunches from the office together and were often berated by the other children for being poor. I made friends with a group of white girls, but since they were as prolific as the boys about jokes made at Mexican and Indian expense, I had to keep a distance. The feeling of never really belonging was a lonely one.

It really wasn’t until I was in my early teens that I noticed Native racism becoming more prevalent, probably because my parents started allowing my school friends to come over to our house. I have 52 first cousins. We never really had sleepovers with outside kids until then. We stuck to ourselves. We had school friends that were not allowed on the reservation. Community leaders in the valley made jokes and issued vile commentary regarding ‘the dirty reservation,’ ‘the trailer dump,’ and they made typical generalizations about reservation residents…the alcoholics, the unemployed, the uneducated, those classic Native American stereotypes. We were ‘never going to make it,’ according to them.

I was once told by a teacher that I should become a hairdresser because it was as far as I would go.

In my adulthood, I confront ongoing racism, but there is that little Brown girl in me who sometimes wants to remain silent, unnoticed, fearful that white power is real, that white power still lingers over me, that I am ‘less than’ because I am Chumash and Mexican.

Then, the strong Brown woman in me arises, smiles at my inner child, and she helps me fight for what is right. I continue to bring my language back to my people. Language is the center of my people. We prevail. We are a strong nation. We will overcome. We carry the scars of our ancestors, who endured far more terrible things than schoolyard racism. I ensure my children understand who they are and where they came from, so they develop their voices to speak out against inequalities.”

*Compiled from August 7th, 2020